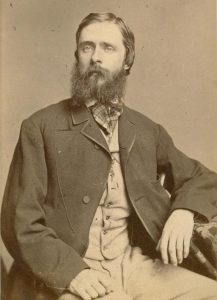

Fitz Hugh Ludlow, 1836-1870 (author, journalist & explorer)

After the civil war, opium addiction became widespread in the United States and in 1868, Horace Day published The Opium Habit, one of the earliest books to deal with the crisis. Friz Hugh Ludlow, famed author of The Hasheesh Eater, submitted a chapter entitled Outlines of the Opium-Cure in which he touted the benefits of cannabis while lamenting its “remarkably variable” potency that sometimes led to “absurd directions” on the bottle labels and ineffectual treatments.

Ludlow describes one case where “the opium-eater under my care was powerfully affected and greatly benefited by the prescription of… cannabis indica” and contrasts it with another patient in whom was observed “no perceptible effect whatever from the absolutely colossal dose.”

Despite the wildly varying potencies and “the fact that its effects vary so wonderfully in different people,” he held out hope that extracts would one day be standardized – “condensed, uniform, and portable” – and he recounted the “repeated proofs of its great value in lulling pain and procuring sleep when all other means had failed with the reforming opium-eater. The earliest effect will be a cerebral stimulus, sufficient to divert the mind from the body’s sufferings during day-light, and the reaction will come on in time to produce slumber of a more peaceful and refreshing character – more nearly like normal sleep in a strong, energetic constitution fatigued by healthy exertion, than that involved by any drug I know of.”

Outlines of the Opium-Cure (excerpts)

by Fitz Hugh Ludlow

(from The Opium Habit – With Suggestions as to the Remedy, by Horace Day. Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1868)

Notice, by way of illustration, the fact that one opium-eater under my care was powerfully affected and greatly benefited by the prescription of one drachm of the fluid extract of cannabis indica, while another, in temperament, history, tendencies, and all but a few apparently trifling particulars almost identical, not only received no benefit but actually experienced no perceptible effect whatever from the absolutely colossal dose of four fluid ounces*

* I am aware how incredible this statement will seem to those who have never had any extensive experience of the behavior of this remarkably variable drug, and get their notion of its action from the absurd directions on the label of every pound vial I have seen sent forth by our manufacturing pharmaceutists. “Ten to twenty drops at a dose,” they say, “cautiously increased.” Cannabis should always be used with caution, but ten or even twenty drops must be inert in all but the rarest cases, and I have given an ounce per diem with beneficial effect. But four ounces of the best extract (Hance & Griffith’s) producing literally no effect of any kind on an entirely fresh subject, is a phenomenon that I must have needed eye-witness to imagine possible.

—-

There may be many alleviatives by which the suffering may be rendered more endurable… The greatest variety of opinions prevails upon the subject of cannabis and scutellaria. The principal objection to the cannabis lies in two facts. First, it is very difficult to obtain any two consecutive specimens of the same strength, even from the same manufacturer. Second, in its gum state it is exceedingly slow of digestion, and unlike opium not seeming to affect the system at all by direct absorption through the walls of the stomach, it is very slow in its action; the dose you give at 4 P.M. may not manifest itself till 9 or even midnight, and even then may still move so sluggishly that you get from it only a prolonged, dull, unpleasant effect instead of a rapid, favorable, and well-defined one. If it is given in the form of a fluid extract or tincture, its operation can be more definitely measured and counted on, but the amount of alcohol required to dissolve it is sufficient often to complicate its effects very prejudicially, while in any case the immense proportion of inert rubbish, gum, green extractive, woody fibre, and earthy residuum is so great as to be a severe tax on the digestive apparatus—often seriously to derange the stomach of the well man who uses it, and much more the exquisitely sensitive organ of the opium-eater, I might add a third objection-the fact that its effects vary so wonderfully in different people—but the physician can soon get over that by making his patient’s constitution in the course of a few experiments with the drug the subject of his careful study.

Both its lack of uniformity and its difficulty of exhibition may be nullified by using the active principle. It has been one of the opprobria medicinæ that in a drug known to possess such wonderful properties so little advance has been made toward the isolation of the alkaloid or resinoid on which it depends for its potency. I have for years been endeavoring to interest some of our great manufacturing pharmaceutists in the attainment of a form—condensed, uniform, and portable—which should stand to cannabis in the same relation which morphia bears to opium. I believe that, in collaboration with my friend Dr. Frank A. Schlitz (a young German chemist of remarkable ability and with a brilliant professional career before him), I have at last attained this desideratum. I have no room or right here to dwell upon this interesting discovery further than to say that we have obtained a substance we suppose to bear the analogy desired and to deserve the title of Cannabin. If further examination shall establish our result, we have in the form of grayish-white acicular crystals a substance which stands to cannabis in nearly the same proportional relation of potency as niorphia to opium, and this most powerful remedy can be given as easily and certainly as any in the pharmacopoeia. If we are successful we shall ere long present it to the medical profession. With all the objections that prejudice cannabis now, I have still witnessed repeated proofs of its great value in lulling pain and procuring sleep, when all other means had failed with the reforming opium-eater, in doses of from one drachm to five of fluid extract or tincture (in some rare cases even larger), administered twice a day. Like opium it is only secondarily a soporific, and to produce this effect it should be given three or four hours before the intended bed-time. Then the earliest effect will be a cerebral stimulus, sufficient to divert the mind from the body’s sufferings during day-light, and the reaction will come on in time to produce slumber of a more peaceful and refreshing character—more nearly like normal sleep in a strong, energetic constitution fatigued by healthy exertion, than that invoked by any drug I know of.