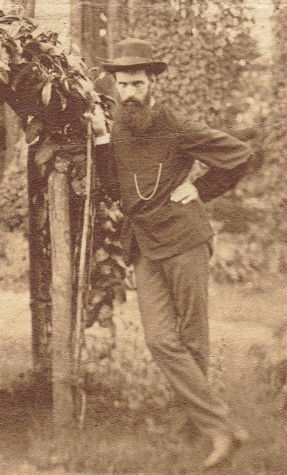

Sir William Mackworth Young, president of the Commission, seen here exploring India in his younger years

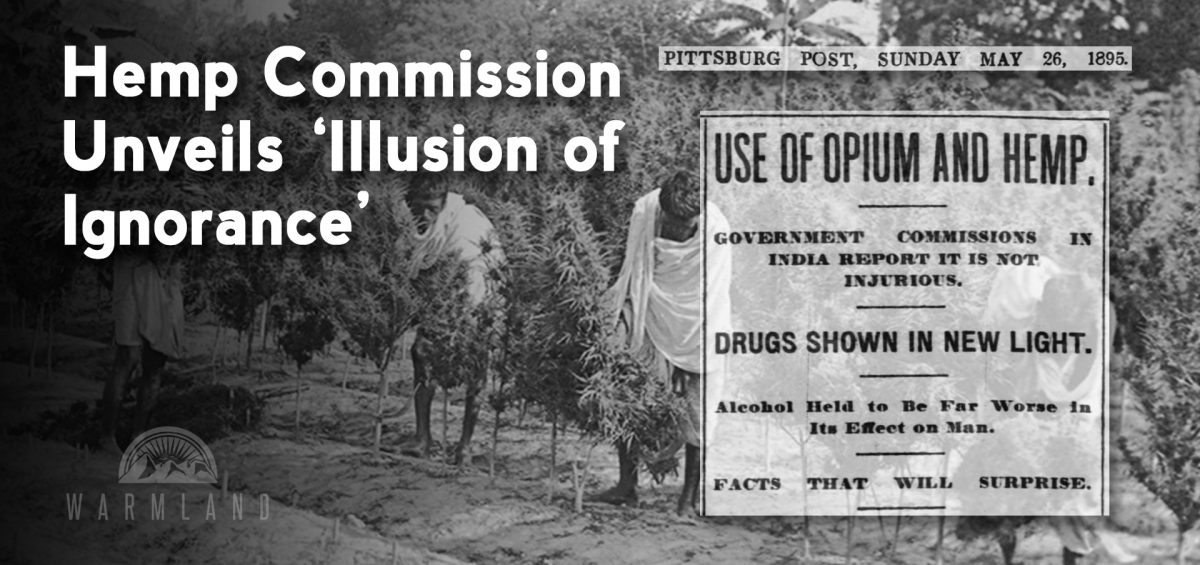

In the early 1890s, the British government grew concerned over the use of “hemp drugs” in India after hearing reports its users were filling asylums. Before long, the Government of India appointed a seven-member royal commission, the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission, to thoroughly investigate the mental, physical, moral and societal costs associated with cannabis use throughout the country.

The Commission was led by Sir William Mackworth Young, a member of the Imperial Legislative Council and future Lieutenant-Governor of the Punjab. Young knew India well, having served there for over 30 years with Britain’s elite administrative arm, the Imperial Civil Service. He was a perfect choice, and he was handed the resources to get the job done right.

Facts Combine Most Clearly

Young’s team scoured the country, interviewing nearly 1,200 “doctors, coolies, yogis, fakirs, heads of lunatic asylums, bhang peasants, tax gatherers, smugglers, army officers, hemp dealers, ganja palace operators and the clergy.” They accumulated a wealth of knowledge that took 3,281 pages to summarize in their 1894 report. However, their ultimate conclusion was surprisingly simple: cannabis is relatively harmless and should not be prohibited.

“The moderate use of hemp drugs is practically attended by no evil results at all… It has been the most striking feature in this inquiry to find how little the effects of hemp drugs have obtruded themselves on observation. The facts combine to show most clearly how little injury society has hitherto sustained from hemp drugs.”

‘Illusion of Ignorance’

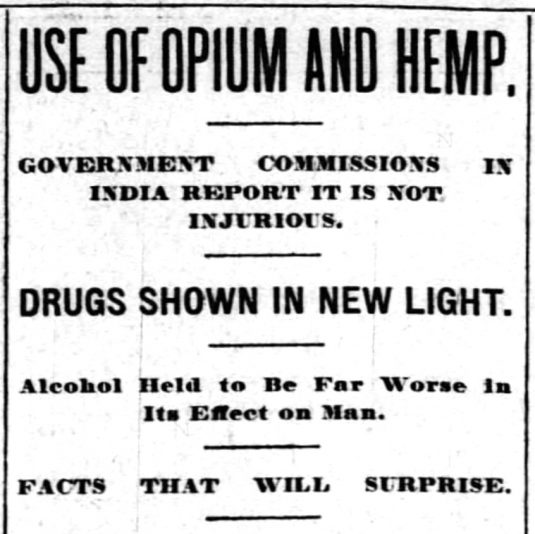

News of the report gradually spread, receiving newspaper coverage on both sides of the Atlantic. On May 26, 1895, the Pittsburgh Post reprinted a feature from the London Spectator which highlighted the Commission’s startling findings:

Pittsburgh Post, May 26, 1895

“The report on the consumption of hemp, made by a commission appointed by the Indian government, is, to us, we confess, a surprise – we were under the definite impression that the extracts of hemp, in whatever form consumed, were invariably pernicious, the drug, taken in moderation, destroying the nerves, and, taken in excess, producing homicidal mania… That impression, however, turns out to be an illusion of ignorance.

The Indian government, which has no motive whatever for protecting the sale of the hemp products, has ascertained, after careful investigation, that their use in the majority of cases has no result whatever either on health or morals; and that even when taken in excess they produce no more crime than alcohol does, which, as all the native witnesses testify, would be the immediate alternative. Unless, therefore, the government of India were prepared to prohibit all stimulants alike it cannot prohibit the sale of the hemp products, which, again, are protected by their use among certain castes in religious ceremonials, with which we cannot interfere.”

Although the Commission’s report seems to have done little, ultimately, to stem the tide of cannabis prohibition in the West, it helped keep prohibition at bay in India where, for the next century, it was generally taxed instead of prohibited.

Select Photographic Plates from the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission Report

A hemp shop proprietor displays “bhang, ganja and majum” in Khandesh, India (1894)

Labourers gather a ganja crop in Naogaon, India (1894)

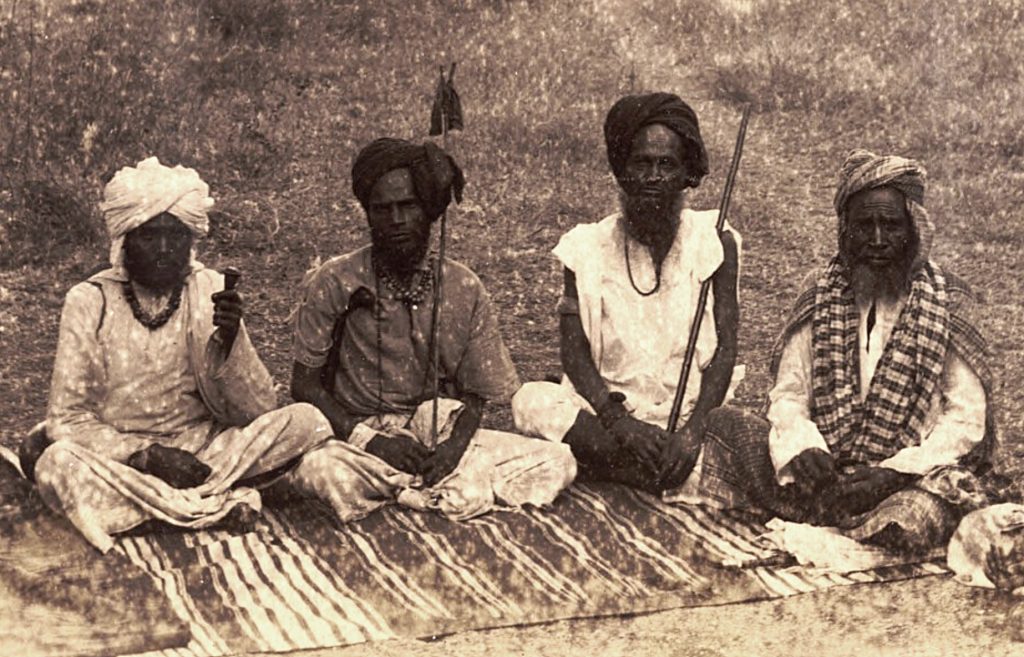

These fakirs in Khandesh, India, were categorized as “habitual moderate ganja smokers.” (1894)

Spontaneous growth of cannabis in the public garden at Amritsar, India (1894)

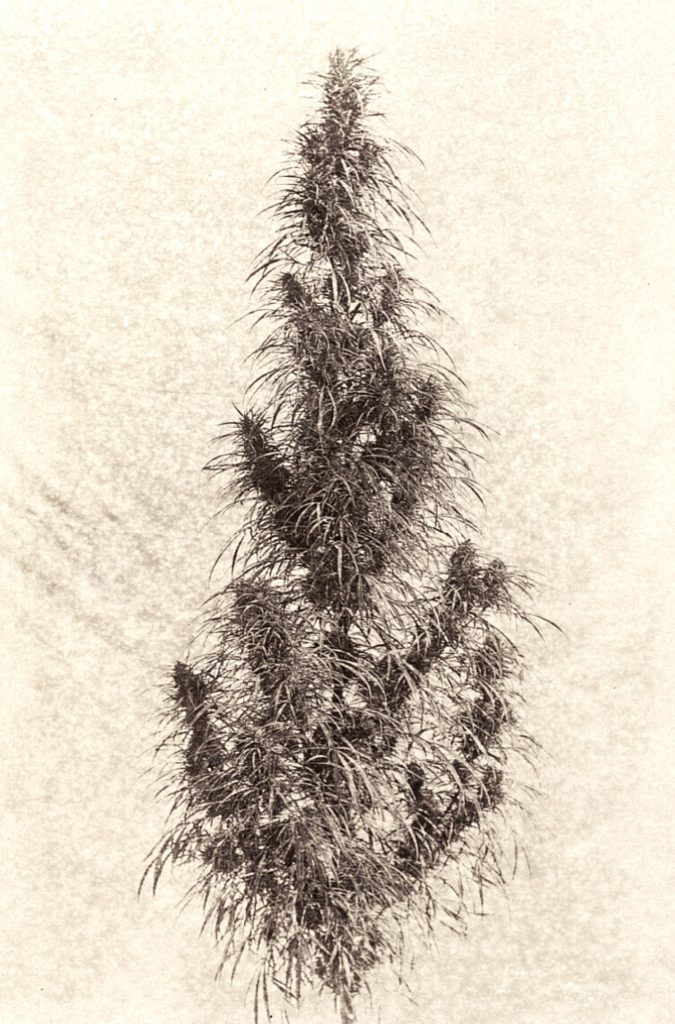

A ganja plant nearly ready to harvest in Naogaon, India (1894)