In the middle of the 19th century, American author Bayard Taylor was exploring Egypt. After hearing frequent mentions of the “curious effects produced by hasheesh”, he grew curious and took what his guide, Achmet, considered to be a “large dose… a preparation made from the cannabis indica.” Waiting only half an hour, Taylor grew impatient and made the classic mistake of doubling up his dose before the first kicked in…

For a time, Taylor was completely immobilized. “No sum could have tempted me to move a finger. The slightest shock seemed enough to crush a structure so frail and delicate as I had become.” Before long, everything took on a “ridiculous light” and “at last it seemed to me that my eyes were increasing in breadth.”

Pondering such absurdity, Taylor blurted out, “Achmet, how is this? My eyes are precisely like two onions.” He then “laughed so loud and long at the singular comparison I had made, that when I ceased from sheer weariness the effect was over.”

Taylor undoubtedly slept well that evening, and in the morning he discovered that his eyes seemed back to normal. Even better, his writer’s block had vanished: “I was able to write for the first time in a week.”

Bayard Taylor (Putnam’s Monthly Magazine, August 1854)

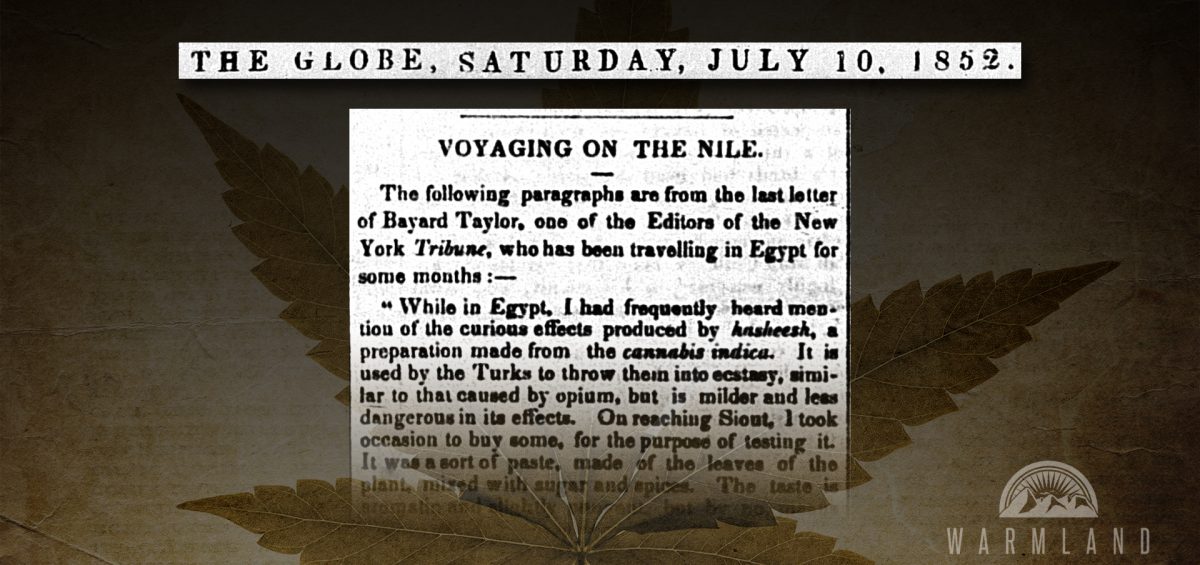

VOYAGING ON THE NILE

The Globe, July 10, 1852

The following paragraphs are from the last letter of Bayard Taylor, one of the Editors of the New York Tribune, who has been travelling in Egypt for some months: —

“While in Egypt, I had frequently heard mention of the curious effects produced by hasheesh, a preparation made from the cannabis indica. It is used by the Turks to throw them into ecstasy, similar to that caused by opium, but is milder and less dangerous in its effects. On reaching Siout, I took occasion to buy some, for the purpose of testing it. It was a sort of paste, made from the leaves of the plant, mixed with sugar and spices. The taste is aromatic and slightly pungent, but by no means disagreeable. About sunset, I took what Achmet considered to be a large dose, and waited about half an hour without feeling the slightest effect. I then repeated it, and drank a cup of hot tea immediately afterward. In about ten minutes I became conscious of the gentlest and balmiest feeling of rest stealing over me. The couch on which I sat grew soft and yielding as air; my flesh was purged from all gross quality, and became a gossamer filagree of exquisite nerves, every one tingling with a sensation which was too dim and soft to be pleasure, but which resembled nothing else so nearly. No sum could have tempted me to move a finger. The slightest shock seemed enough to crush a structure so frail and delicate as I had become. I felt like one of those wonderful sprays of brittle spar which hang for ages in the unstirred air of a cavern, but are shivered to pieces by the breath of the first explorer.

As this sensation, which lasted but a short time, was gradually fading away, I found myself infected with a tendency to view the most common objects in a ridiculous light. Achmet was sitting on one of the provision chests, as was his custom of an evening. I thought: was there ever anything so absurd as to see him sitting on that chest? And laughed immoderately at the idea. The turban worn by the captain next put on such a quizzical appearance that I chuckled over it for some time. — Of all turbans in the world it was the most ludicrous. Various other things affected me in like manner, and at last it seemed to me that my eyes were increasing in breadth. ‘Achmet,’ I called out, ‘how is this? My eyes are precisely like two onions.’ I laughed so loud and long at the singular comparison I had made, that when I ceased from sheer weariness the effect was over. But on the following morning my eyes were much better, and I was able to write, for the first time in a week.”

Siout, Egypt, by Sanford Robinson Gifford, 1823 – 1880, 1874, oil on canvas. Source: National Gallery of Art.